Adoption of HTTP Security Headers on the Web

Over the past few weeks the topic of security related HTTP headers has come up in numerous discussions – both with customers I work with as well as other colleagues that are trying to help improve the security posture of their customers. I’ve often felt that these headers were underutilized, and a quick test on Scott Helme’s excellent securityheaders.io site usually proves this to be true. I decided to take a deeper look at how these headers are being used on a large scale.

Looking at this data through the lens of the HTTP Archive, I thought it would be interesting to see if we could give the web a scorecard for security headers. I’ll dive deeper into how each of these headers are implemented below, but let’s start off by looking at the percentage of sites that are using these security headers. As I suspected, adoption is quite low. Furthermore, it seems that adoption is marginally higher for some of the most popular sites – but not by much.

The HTTP Archive query behind the data in the table is below, and you can see the full query here.

SELECT count(distinct p.pageid) pages,

ROUND(SUM(IF(LOWER(r.respOtherHeaders) LIKE "%strict-transport-security%",1,0))/count(distinct p.pageid),3) HSTS,

ROUND(SUM(IF(LOWER(r.respOtherHeaders) LIKE "%content-security-policy%",1,0))/count(distinct p.pageid),3) ContentSecurityPolicy,

ROUND(SUM(IF(LOWER(r.respOtherHeaders) LIKE "%x-frame-options%",1,0))/count(distinct p.pageid),3) XFrameOptions,

ROUND(SUM(IF(LOWER(r.respOtherHeaders) LIKE "%x-xss-protection%",1,0))/count(distinct p.pageid),3) XSSProtection,

ROUND(SUM(IF(LOWER(r.respOtherHeaders) LIKE "%x-content-type-options%",1,0))/count(distinct p.pageid),3) ContentTypeOptions,

ROUND(SUM(IF(LOWER(r.respOtherHeaders) LIKE "%referrer-policy%",1,0))/count(distinct p.pageid),3) ReferrerPolicy

FROM `httparchive.runs.2018_02_01_requests` r

JOIN (

SELECT rank, pageid FROM `httparchive.runs.2018_02_01_pages`

) as p

ON p.pageid = r.pageid

WHERE firstHtml = true and rank > 0 and rank < 1000

The chart was generated with a similar query, but adding ROUND(rank/1000)*1000 as rankgroup, to the SELECT clause. You can find that query here.

So, How Are these Headers Being Used in the Wild?

The httparchive.har.2018_02_01_chrome_requests table contains all of the HTTP request and response headers for every single object. The table size is quite large (> 100GB), so to start off this phase of the analysis I created a smaller table based on it. The query I used is here, and it allowed me to work with a subset of this data. I used the indicator _final_base_page=true to collect just the HAR entries for the base page requests. Now I’m working w/ a 1.5GB table.

So let’s dig into what these headers do, and how they are being used…

Strict-Transport-Security (HSTS)

Strict Transport Security (HSTS) tells the browser that the current page should always be loaded via HTTPS. When the browser recognizes this then it will never attempt an HTTP request to the affected domain. If you test this in DevTools, you’ll see an HTTP 307 internal redirect from http->https – because the HTTP request never went out to the network. This is incredibly effective at preventing MiTM attacks. You can use the includeSubdomains directive to secure all sudomains. The preload directive also allows supported browsers to include your preference for HTTPS in the browser distribution. More details on the HSTS header https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc6797, and the preload feature https://hstspreload.org/.

I found 44,003 sites that include an HSTS header on their homepage and all of them contained a max-age header (which is required). However not all of the max-age headers were defined correctly or long enough to matter. Almost 2,300 sites configured their max-age to 0 seconds – which effectively withdraws their sites from HSTS. Some sites had typos in the directives, garbled text and even some negative values. Overall, 84% of sites using HSTS are setting the max-age directive for at least 1 week.

Additionally, 35% of sites using HSTS are using the includeSubdomains directive. And 18% had the preload directive included.

Content-Security-Policy (CSP)

Content Security Policy (CSP) allows you to set a policy that controls what type of content is allowed to be loaded from your site. This provides an added layer of security that can help to detect and mitigate XSS attacks, data injection attacks, and preventing the loading of content that you do not explicitly allow. This can protect against data theft, defacement, and malware distribution. You can read more about CSP here.

At the start of this post, we learned that only 2.9% of sites in the HttpArchive make use of CSP headers. These 13,598 sites have vastly different CSP directives defined, which is expected. There are also 1523 sites that use the Content-Security-Policy-Report-Only directive – which only reports on the violations and doesn’t enforce them.

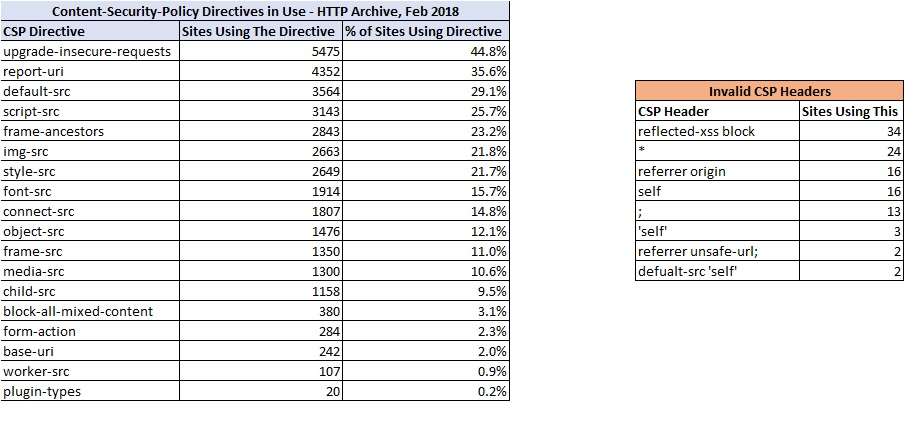

So which CSP directives are in use today? The below table summarizes the popular directives used on sites, as well as an example of some invalid CSP headers.

You’ll probably notice some typos in the invalid CSP Headers table. However the 34 sites using reflected-xss-block are rather interesting. It seems this was part of an early draft of CSP, but was deprecated in favor of X-XSS-Protection. More details on that here – https://bugs.chromium.org/p/chromium/issues/detail?id=657737

X-Frame-Options

The X-Frame-Options header allows you to indicate whether or not a browser should allow your pages to render in a <frame>, <iframe> or <object>. This helps prevent clickjacking attacks since it can prevent your content from being embedded into another site. There are three different values for the header field, and according to the RFC they must be mutually exclusive, ie set to exactly one of the 3 values.

In the table below you can see that 98% of the time this is configured correctly. 87% of sites that include it are using X-Frame-Options: SameOrigin. 10% use the X-Frame-Options: Deny header. And 1% are specifically allowing domains via X-Frame-Options: Allow-From. There are a small % of sites that are using incorrect directives, even 70 sites that are using X-Frame-Options: GOFORIT.

A quick Google search for the GOFORIT example revealed a StackOverflow post where someone recommended using this to invalidate X-Frame-Options and force the browser to fail-open. One can only hope that those implementing it on their sites understand that they are effectively disabling this security feature…

X-XSS-Protection

The X-XSS-Protection header stops pages from loading when they detect reflected cross-site scripting (XSS) attacks. The value can be set to 0 (disable the protection) or 1 (default, enable the protection). Additionally, you can set it to 1;block to both enable the protection and tell the browser not to load the page. If block is not present, then the browser will remove the unsafe references and attempt to continue loading the page. And for Chrome browsers you can set it to 1;report=<uri> which will use the reporting functionality in CSP to send a report of the violation. You can read more about this header and see some examples here.

So how are we doing? Out of 48,009 sites that are using this header, 91% are configuring it to block the loading of their sites during XSS attacks. In fact the most common way of setting it is 1; mode=block. However there are 1206 sites that set it to `` which effectively removes protection. Even more concerning are the 145 sites that set it to 0; mode=block since the browser will not block the attack because of the 0 setting…

X-Content-Type-Options

The X-Content-Type-Options header is used to tell the browser that it should prevent loading a resource if there is a mismatch between the content-type response header and the destination for the object. For example, this would prevent </p>

The only valid syntax for this header is X-Content-Type-Options: nosniff. 99.95% of the time this is being set correctly.

Referrer-Policy

The Referrer-Policy HTTP header governs which referrer information, if any, should be included in the Referer header of requests made from the site. More details on this header along with some great examples of what all the directives mean are here as well as in the specification here.

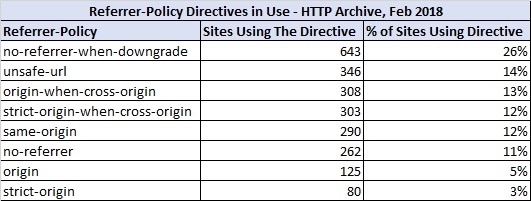

Most browsers default to no-referrer-when-downgrade, which means that the referrer is included on HTTP requests when the protocol security stays the same (ie, an HTTPS->HTTPS). The table below summarizes how they are configured across other websites. These add up to 97%, as another 3% have incorrectly configured their Referrer-Policy headers.

Conclusion

There’s a lot that we can do with these security headers – but based on the data in the HTTP Archive it’s pretty clear that they are not being used enough and sometimes are being used incorrectly. I learned a few things along the way while doing this analysis and I hope you found this useful as well. If you’d like to discuss some of these findings or if I missed something, please comment on the HTTP Archive thread linked below!

Originally published at https://discuss.httparchive.org/t/adoption-of-http-security-headers-on-the-web/1259/