Choosing Between gzip, Brotli and zStandard Compression

HTTP compression is a mechanism that allows a web server to deliver text based content using less bytes, and it’s been supported on the web for a very long time. In fact the first web browser to support gzip compression was NCSA Mosaic v2.1 way back in 1993! The web has obviously come a long way since then, but today pretty much every web server and browser still supports gzip compression.

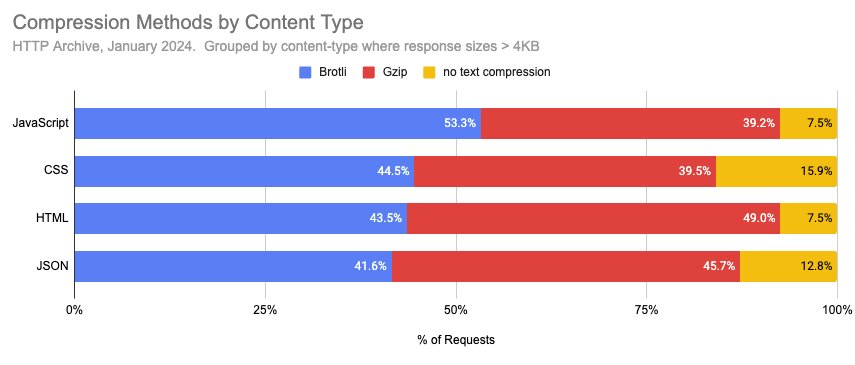

In recent years, new and innovative compression methods have gained browser support. One in particular that has achieved widespread adoption is Brotli. First supported in Chrome 50 (2016), it was supported by all modern browsers a year later. Brotli is able to compress files much smaller than gzip, albeit with a higher computational overhead. Based on HTTP Archive data from January 2024, Brotli is actually used more than gzip for JavaScript and CSS!

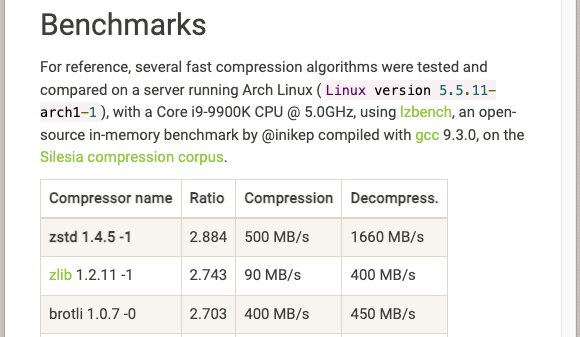

Facebook’s zStandard compression is another promising new method which aims to serve smaller payloads compared to gzip while also being faster. zStandard was added to the IANA’s list of HTTP content encodings with an identifier of “zstd”, and support for it was added to Chrome in version 123, which was released this month. Facebook recently shared some benchmarks that show it performing signifcantly faster than gzip.

Beyond this, there’s also shared dictionaries for Brotli and zStandard, which have the potential to significantly reduce byte sizes.

While it may take some time for browsers, web servers and CDNs to catch up, it’s worth pondering which compression method is right for your content. A few years ago I wrote a blog post about Brotli compression as well as a tool to help you determine how Brotli could compress your content relative to gzip. I’ve updated this tool to include zStandard compression as well as show the relative latency incurred at each compression level. You can find the new/updated tool at https://tools.paulcalvano.com/compression-tester/

How HTTP Compression Works

When a client makes an HTTP request, it includes an Accept-Encoding header to advertise the compression encodings it can support. The web server then selects one of the advertised encodings that it also supports and serves a compressed response with a Content-Encoding header to indicate which compression was used.

In the example below, the client advertised support for gzip, Brotli, and Deflate compression. The server returned a gzip compressed response containing a text/html document.

GET / HTTP/2

Host: httparchive.org

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, br

HTTP/2 200

content-type: text/html; charset=utf-8

content-encoding: gzip

If a client sends multiple encodings in its Accept-Encoding header, then the server will have to choose one. For example, if I send an HTTP request to Facebook’s homepage and advertise support for gzip, Brotli and zStandard - their server chooses to deliver the response via zStandard.

GET / HTTP/2

Host: www.facebook.com

accept-encoding: gzip, deflate, br, zstd

HTTP/2 200

content-encoding: zstd

content-type: text/html; charset="utf-8"

Gzip Compression

Gzip is fundamentally supported by all web servers, browsers and intermediaries (CDNs, proxies, etc), mostly by default. Despite how easy it is to serve content gzip compressed, there are a few things to keep in mind:

- Most web servers and CDNs default to gzip compression level 6, which is a reasonable default. Some servers (ie, NGINX) default to gzip level 1, which usually results in faster compression times but results in a larger file. Make sure to check your compression levels!

- Many CDNs can gzip compress resources for you, which is helpful if you missed something on your origin server. Some CDNs enable this by default.

- Some CDNs may decompress and recompress content for you if they need to inspect or manipulate the contents. This may have an impact on your time to first byte (TTFB) especially if the content that needs to be recompressed is large.

Brotli Compression

Brotli compression was created by Google and is supported across all major web browsers. At its highest compression level files can often be reduced 15-25% more than gzip. Higher compression levels come at a significant latency cost though.

Many popular web servers support Brotli via modules. For example, Apache has a mod_brotli module which defaults to level 5. NGINX has a module called ngx_brotli which defaults to level 6. Brotli is supported by a variety of CDNs, albeit in slightly different ways. It’s best to understand how your specific CDN handles this compression algorithm. For example:

- Most CDNs have the ability to serve Brotli compressed payloads from an origin server that supports Brotli.

- This is done by varying the content by the Content-Encoding response header.

- Some CDNs do this by default, others require additional steps.

- Some CDNs can Brotli compress responses even if an origin server does not support Brotli.

- Usually they fetch the result via gzip from your origin.

- Some CDNs can perform on the fly Brotli compression for static and dynamic, usually at specific compression levels they define.

- Some CDNs can pre-compress static content at higher compression levels

While the highest compression levels might be ideal for static content, you’ll want to be careful with dynamic content to avoid impacting your TTFB. Additionally if your CDN offers dynamic Brotli compression, then you may want to determine if the byte savings are worth the latency overhead from decompressing and re-compressing the response at the edge. In some cases it may be best to Brotli compress dynamic content from the origin, or stick with Gzip if your origin doesn’t support Brotli.

zStandard

zStandard is a newer compression method developed by Facebook. It was designed to compress at ratios similar to gzip compression, but with faster compression and decompression speeds. Historically its usage has been mostly filesystem related, however Chrome is the first browser to support it as of March 2024. While most CDNs do not have support for zStandard yet, many could feasibly vary the cache key for origin compressed responses similar to the way they support Brotli.

When examining the top 10k sites in the HTTP Archive, zStandard compression usage appears to be mostly confined to sites owned by Meta such as www.facebook.com, www.instagram.com, www.messenger.com, www.whatsapp.com, etc) and Netflix. The Meta sites are delivering zStandard encoded content to Chrome browsers. Netflix’s appears to default to gzip compression, possibly implementing zStandard as a test.

Compression Tester

A few years ago I wrote a compression tool that was designed to help you determine whether gzip is sufficient for your content, or if Brotli could provide a reduction in payload sizes. I’ve released a new version of this tool that includes zStandard compression as well as compression times for each individual test.

You can find the new/updated tool at https://tools.paulcalvano.com/compression-tester/

When we’re looking at these results, a few things you’ll want to keep in mind are:

- If your content is dynamic / non-cacheable, then it will be very sensitive to any additional latency you add. Higher Brotli and zStandard compression levels can bec computationally expensive, so it’s best to use a more moderate compression level.

- If your content is static / cacheable, then you may want to use higher compression levels.

- Compression settings are typically set on a server and not per request. If you do not have flexibility with setting this at a more granular level, you should go with the lowest common denominator required for all of your content.

Let’s dive deeper into a few examples:

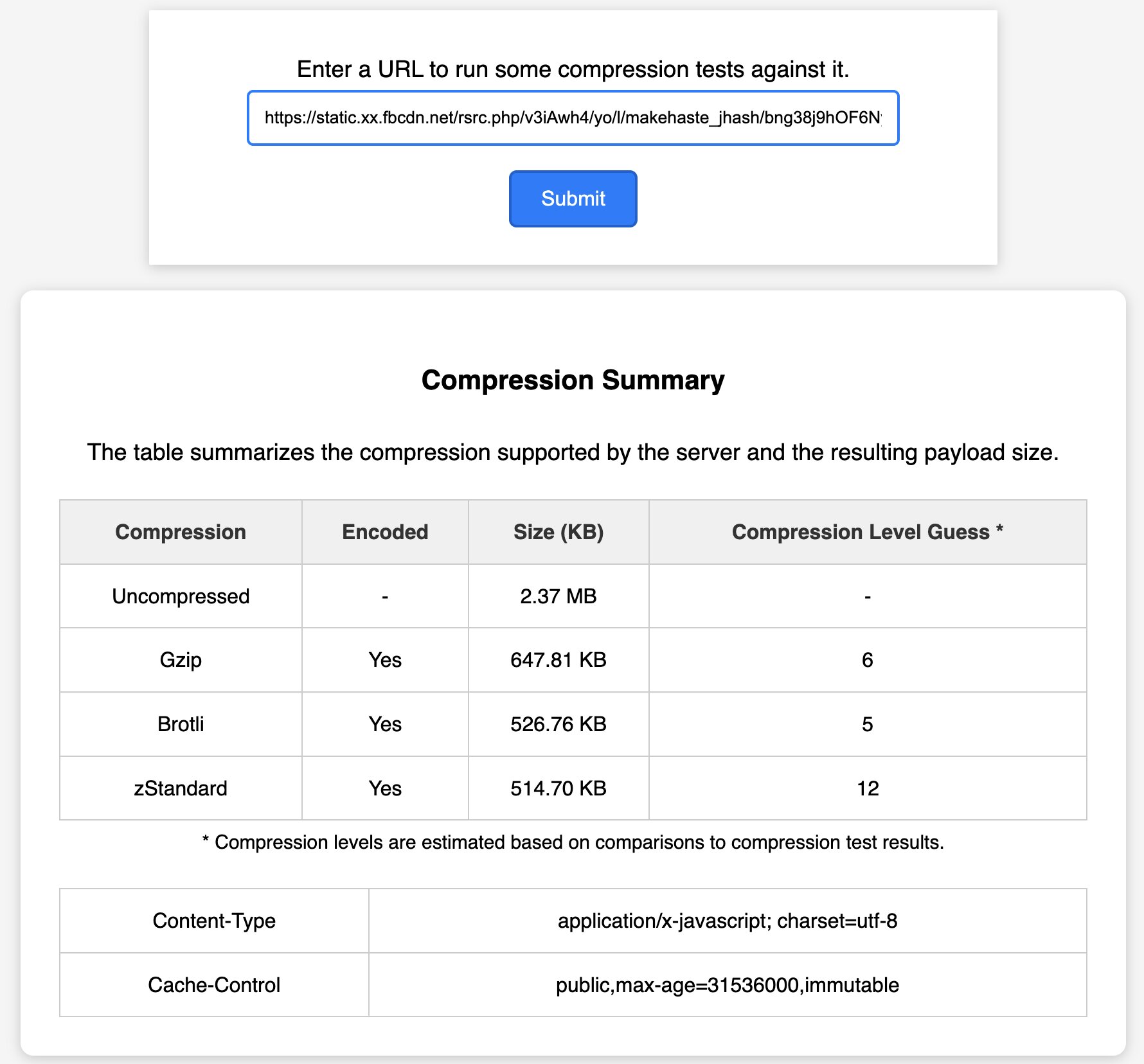

Example: Facebook

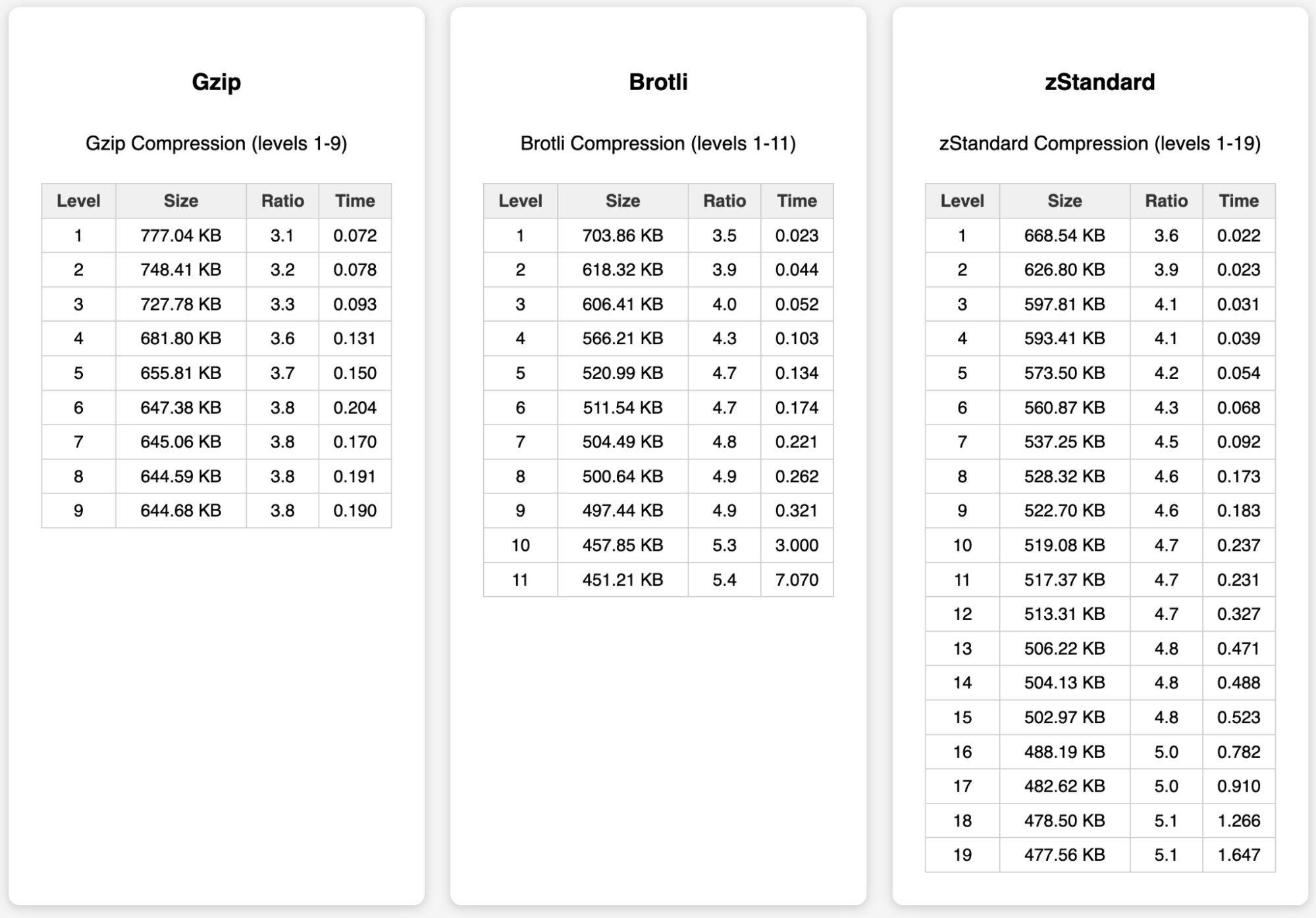

When browsing Facebook, the largest JavaScript resource I saw was 2.37 MB uncompressed. It was delivered to my browser as a 514 KB zStandard compressed response. When testing this file via the Compression Tester tool, it was served a 645 KB gzip and 526 KB Brotli response.

Comparing the compression test results to the delivered responses, we can see that the server likely compressed in the middle range. For example it delivered a 526 KB Brotli payload (presumably level 5), but it could have delivered Brotli level 11 . This would come at a higher computational cost though - which may have been a factor in their selection. zStandard also appears to be delivering a smaller file, but based on this test the computational overhead is more than double what gzip level 6 costs.

For this response, Brotli level 9 would provide the best compression ratio with a CPU overhead similar to zStandard 12. If it’s possible to precompress payloads, then the highest compression levels would reduce the payloads further. However Brotli appears to outperform zStandard in both compression ratio and compression time up until level 9 for this response.

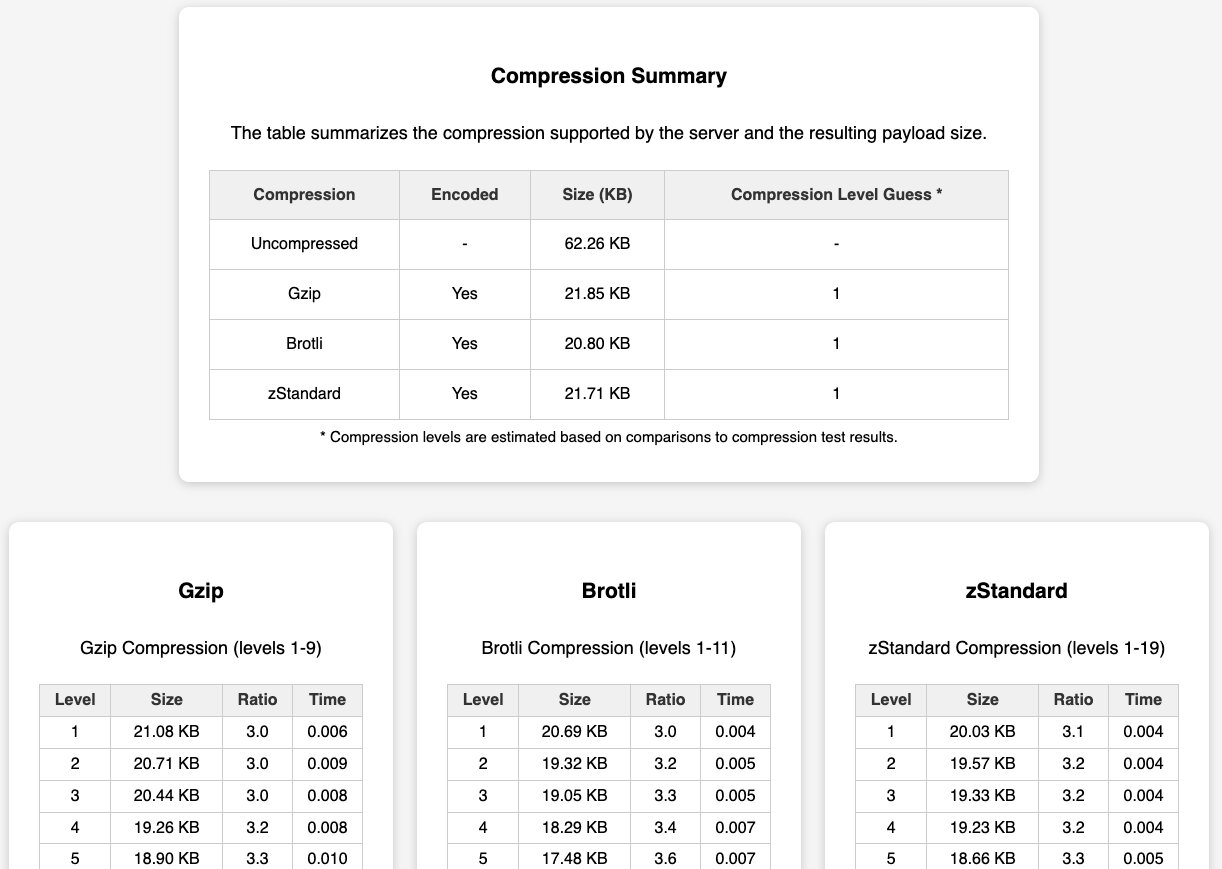

The base HTML page for Facebook, it is 62 KB uncompressed. They support gzip, Brotli and zStandard - and it seems to be compressed at the lowest compression levels. While compression level 1 is often undesired, in this case there doesn’t appear to be much of an advantage of applying higher levels of compression due to limited byte savings. Additionally for Facebook’s HTML all 3 compression algorithms produce a similar size payload - but Brotli and zStandard both compress their HTML faster than gzip.

Sandals.com Homepage

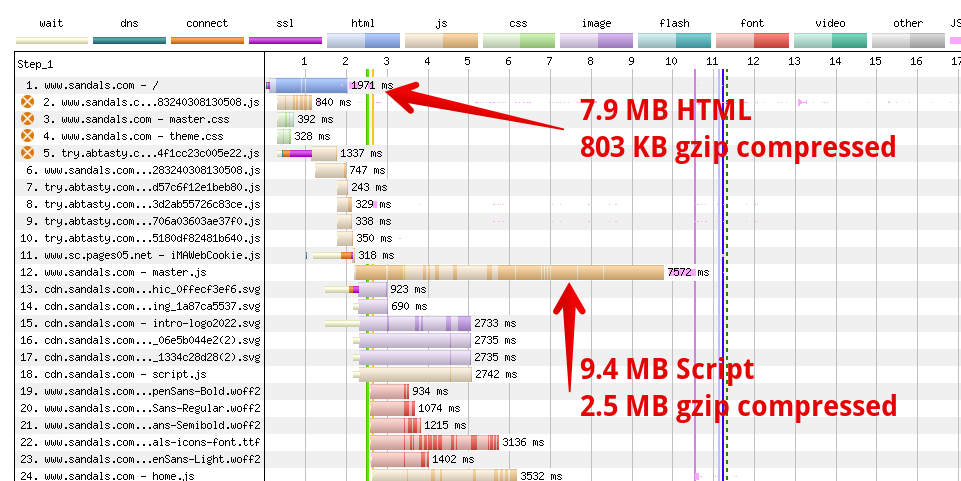

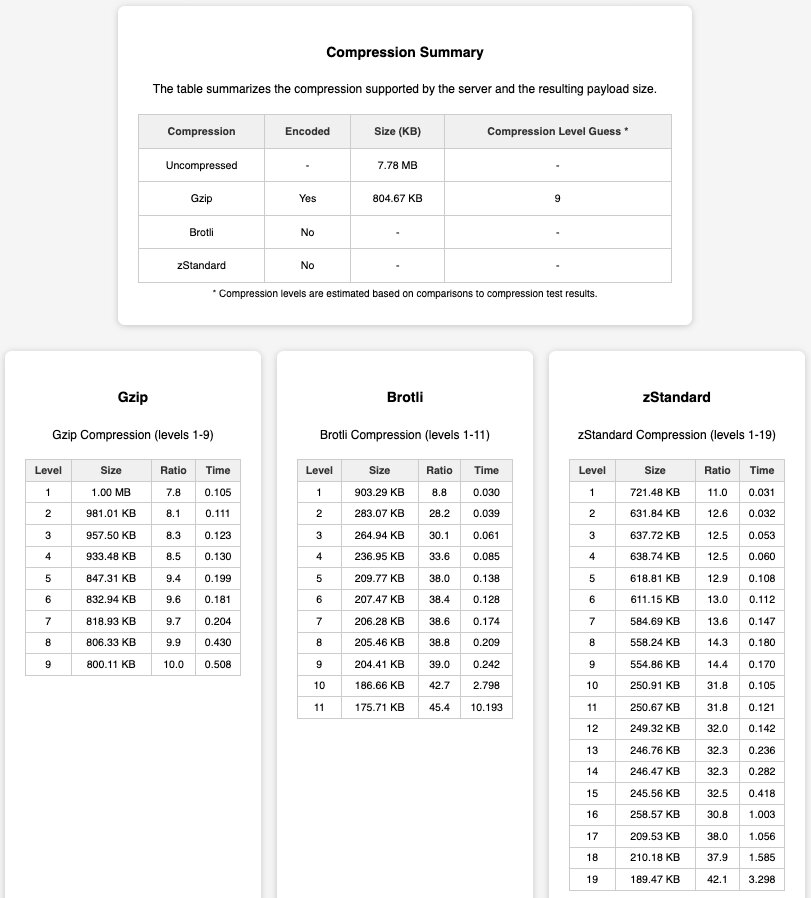

Out of the top 10 thousand websites, Sandals has the largest HTML payload - clocking in at almost 7.9MB (delivered as a 804 KB gzip compressed payload). Additionally they have a 9.4MB script bundle (gzip compressed to 2.5 MB). In the waterfall graph below you can see the impact that these large payloads are having on the experience. Reducing them solves only part of the problem, as that’s still a huge amount of content for the browser to parse, evaluate, and execute. But let’s see how these compression algorithms do.

Sandals appears to be gzip compressing at the highest possible compression level. If we assume that this page is dynamically generated and try to stay within the relative compression times:

- Brotli level 9 or zStandard level 15 would result in approximately 75% smaller payload with faster compression times compared to gzip 9.

- Brotli level 5 appears to be a good tradeoff between compression ratio and time (209 KB, and 73% faster to compress)

- In this particular example, zStandard is producing a larger payload compared to Brotli.

Sandal’s is also using Cloudflare’s CDN which supports Brotli compression, so enabling this could be a quick performance win for them.

Compression Levels vs Compression Times

When considering a compression level, it’s important to balance the time it takes to compress a payload with the estimated byte savings. For example, utilizing the maximum compression level will often produce the smallest payload, but will do so at a higher computational cost. Likewise, the lowest compression levels are often really fast to compress, but might not be as effective.

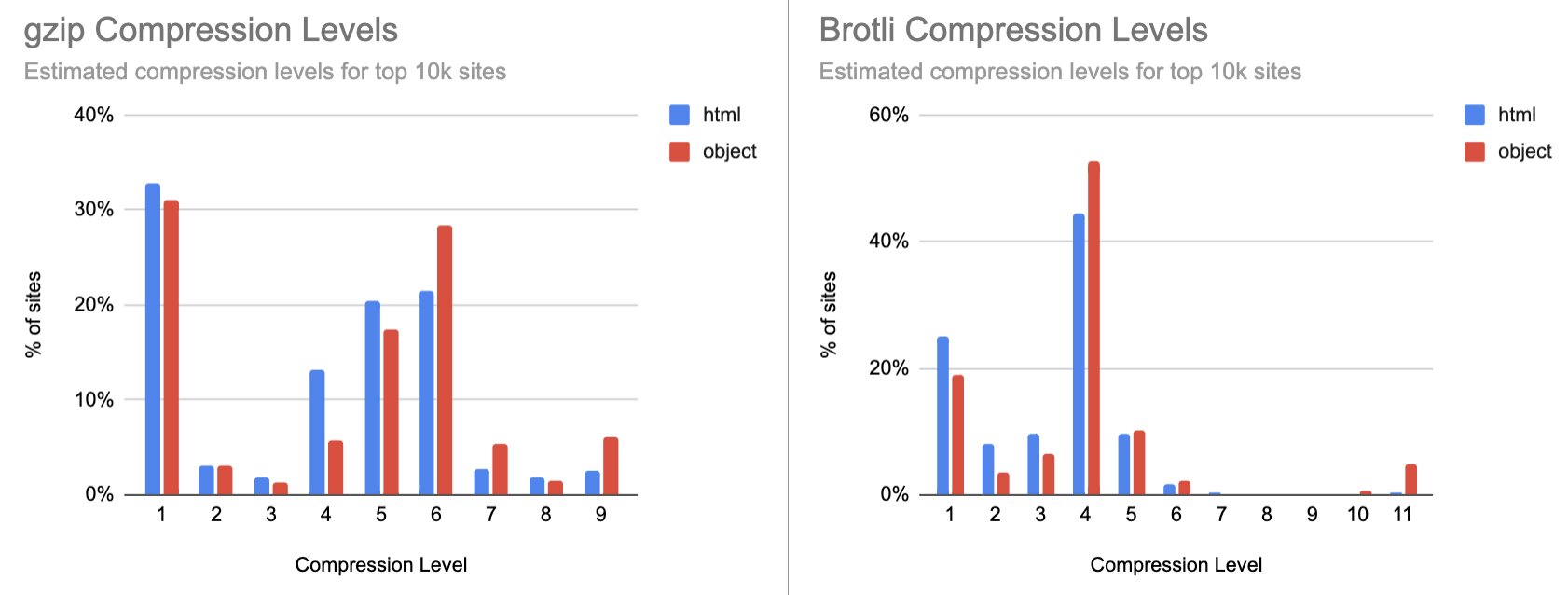

I tested the base HTML of the top 10 thousand websites’ HTML pages and their largest first party request. The results below show that the majority of gzip compression seems to fall within the estimated range of 4-6 (likely 6 since that is a common default). However ~30% of sites are utilizing gzip level 1, which often provides inadequate compression. The majority of Brotli compression appears to be level 4. However there’s ~25% of sites delivering Brotli level 1. And finally the majority of Brotli level 11 usage seems to be for static content.

The table below details a few sites that are serving their HTML using either gzip or Brotli level 1. Using such a low compression level will likely result in larger payload. In many of these examples, the Brotli compressed payload is actually larger than gzip. Fortunately some of these sites are leveraging services that will automatically deliver gzip because of the byte discrepancy - but they could still benefit from increasing the compression level.

| Content Length Delivered (KB) | |||

| url | Uncompressed | gzip | Brotli |

| https://www.epicurious.com | 3877 | 393 | 684 |

| https://www.anker.com | 3273 | 628 | 232 |

| https://www.bonappetit.com | 1889 | 230 | 348 |

| https://www.allure.com | 1817 | 239 | 372 |

| https://www.gq.com | 1665 | 226 | 340 |

| https://www.newyorker.com | 1638 | 252 | 342 |

| https://www.vanityfair.com | 1593 | 231 | 339 |

| https://seekingalpha.com | 1453 | 279 | |

| https://www.vogue.com | 1446 | 204 | 312 |

| https://www.cntraveler.com | 1422 | 205 | 311 |

The table below shows the results of applying gzip level 6, brotli level 5 and zStandard level 12 against the base HTML on these pages A few observations:

- Gzip level 6 reduces most of the gzipped payloads by 25-30% compared to the size delivered via gzip level 1.

- Brotli level 5 was able to reduce their sizes by almost 75% compared to gzip level 1. In many cases the compression time overhead is comparable to gzip level 6 - but this varies.

- zStandard level 12 was able to provide similar compression levels to brotli level 5 while maintaining compression times similar to gzip level 6.

Based on these examples, real time zStandard compression seems to provide a slight advantage over Brotli - achieving the same sizes with faster compression times.

| >After applying higher compression levels | Compression Time (seconds) | |||||

| url | gzip (L6) | Brotli (L5) | zStd (L12) | gzip (lL6) | Brotli L5) | zStd (L12) |

| https://www.epicurious.com | 271 | 145 | 145 | 0.083 | 0.093 | 0.068 |

| https://www.anker.com | 412 | 219 | 219 | 0.099 | 0.081 | 0.088 |

| https://www.bonappetit.com | 169 | 113 | 114 | 0.044 | 0.061 | 0.054 |

| https://www.allure.com | 179 | 135 | 135 | 0.051 | 0.067 | 0.043 |

| https://www.gq.com | 168 | 118 | 119 | 0.049 | 0.053 | 0.050 |

| https://www.newyorker.com | 191 | 127 | 128 | 0.053 | 0.071 | 0.043 |

| https://www.vanityfair.com | 173 | 128 | 128 | 0.058 | 0.098 | 0.042 |

| https://seekingalpha.com | 227 | 171 | 174 | 0.049 | 0.073 | 0.079 |

| https://www.vogue.com | 152 | 115 | 115 | 0.053 | 0.075 | 0.047 |

| https://www.cntraveler.com | 155 | 117 | 117 | 0.052 | 0.052 | 0.048 |

Cacheable objects can often be compressed at higher levels - especially if they are able to be precompressed. When evaluating the largest first party objects hosted on the top 10 thousand sites, I found that Brotli level 5 and zStandard level 12 resulted in similar file sizes and compression times - much like the results above. However when evaluating Brotli compression level 11 vs zStandard 19, the smallest files are almost always generated by Brotli level 11. zStandard’s compression times are 4x faster than Brotli 11 though. So if you have the ability to precompress your objects, Brotli 11 may still be preferred. If not, then zStandard may be the better option.

| % File size reduction compared to gzip level 6 | ||||

| br5 | zstd12 | br11 | zstd19 | |

| Average | 8.85% | 9.07% | 19.18% | 14.11% |

| p50 | 6.99% | 7.33% | 17.53% | 12.40% |

| p75 | 10.25% | 10.94% | 22.21% | 17.10% |

| p90 | 15.29% | 15.74% | 27.21% | 22.40% |

Conclusion

HTTP compression is an incredibly important feature, and has long been overlooked due to the universal support of gzip compression across all web servers and browsers. It’s great to see innovation in this space, and the addition of another compression encoding along with the possibility of shared dictionary compression in the future.

The research I’ve shared in this article also shows that for many sites Brotli will provide better compression for static content. zStandard could potentially provide some benefits for dynamic content due to its faster compression speeds. Additionally:

- A surprising amount of sites are using low level gzip compression, and should consider increasing their compression levels.

- For dynamic content

- Brotli level 5 usually result in smaller payloads, at similar or slightly slower compression times.

- zStandard level 12 often produces similar payloads to Brotli level 5, with compression times faster than gzip and Brotli.

- For static content

- Brotli level 11 produces the smallest payloads

- zStandard is able to apply their highest compression levels much faster than Brotli, but the payloads are still smaller with Brotli.

Of course your mileage will vary and there’s really no universal answer. It’s worth running some tests on your site to see whether your content would benefit, and which compression levels to consider. And then experimenting with RUM data to evaluate whether the approach you decide on is successful. I hope that tool I created helps you get started on this analysis for your site!